Post by marveloushagler on Feb 1, 2007 0:29:39 GMT -5

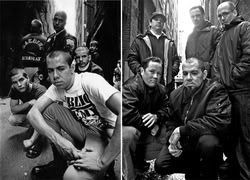

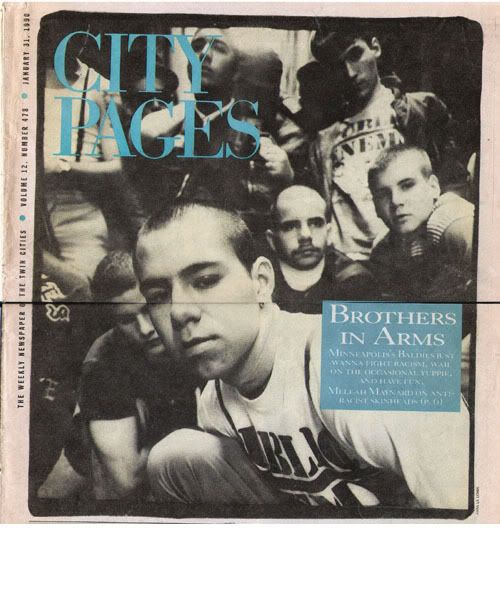

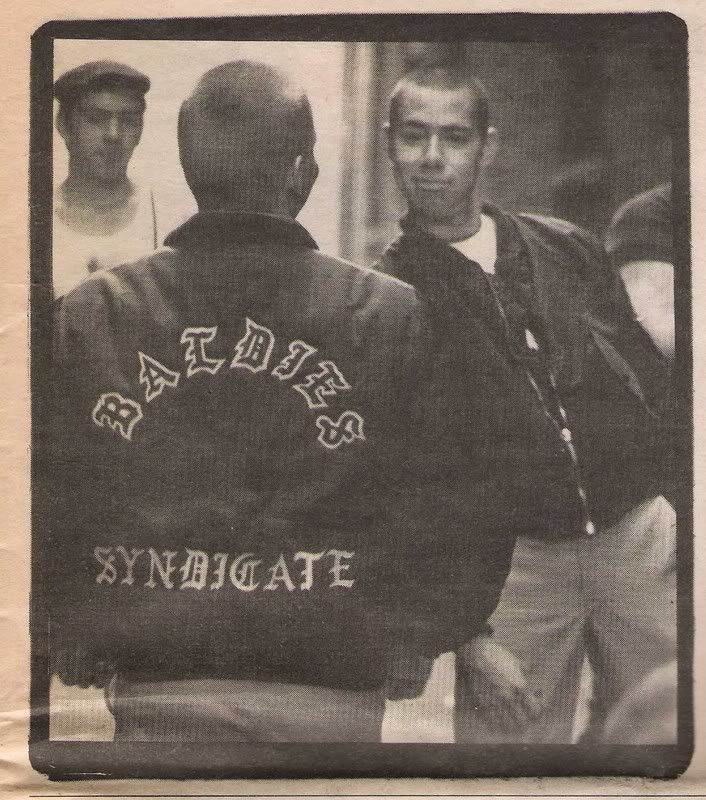

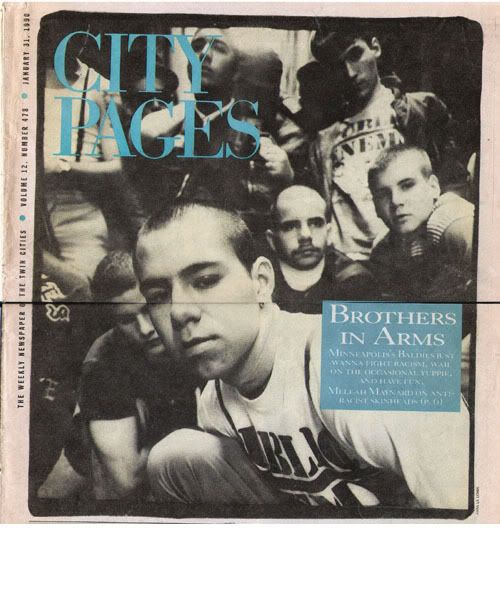

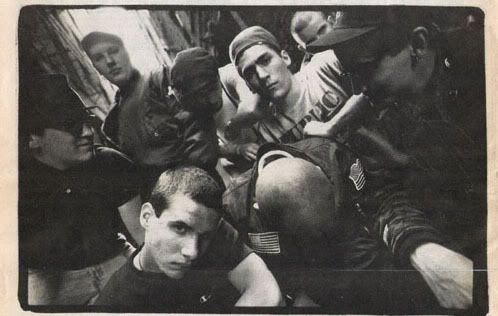

Every once in a while a reporter does an article on skinheads and gets it right. Here’s a classic one from CITY PAGES on the Baldies, Minneapolis’ anti-racist skinhead crew from the late 80’s. They set the bar high for all American anti- racist skinhead crews to come. This was their flagship article from back in the day.

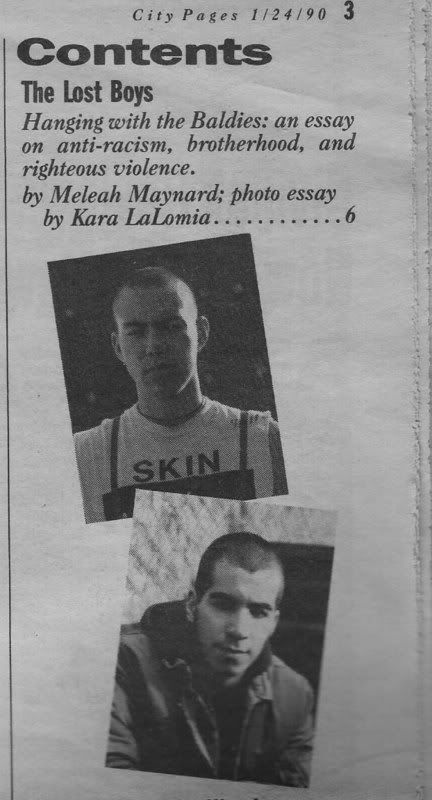

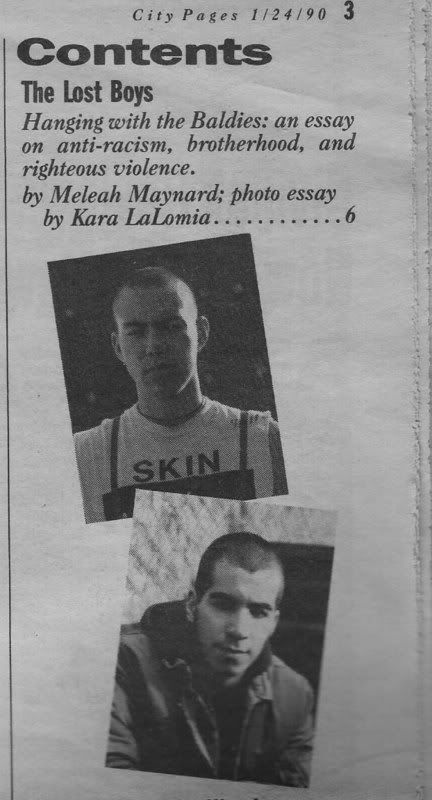

THE LOST BOYS

Anti-racism, brotherhood and righteous violence: the world according to the Baldies.

By Meleah Maynard

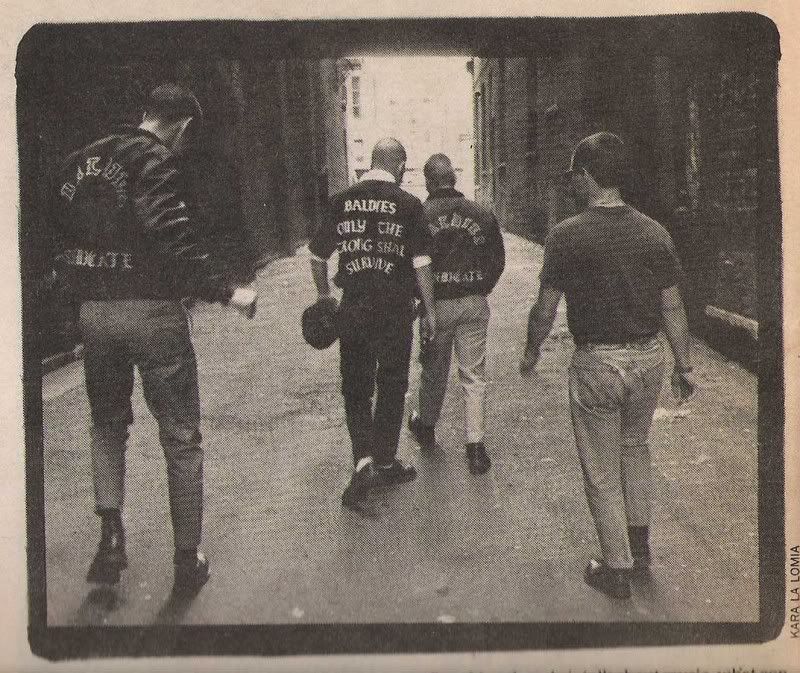

Photos by Kara LaLomia

When Max was in high school, he went to a tattoo parlor and had the word SKIN imprinted inside his lower lip. “Oh, yeah, it hurt like hell at the time,” he grimaces. Without much prompting he sets aside his burger and rolls down his lip to expose the black lettering inside. “I got it because it’s something I believe in,” he says. “Once a skin, always a skin. It’s something that will always be there. It’s a matter of pride.”

After he finishes his burger, Max thinks better of his boast. “Can you change my name in the story?” he asks. “I’m afraid my mom would get made if she knew.” Okay- Max isn’t his real name.

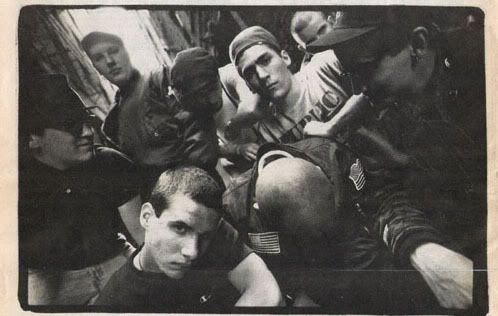

Max’s friends Joe Hawkins and Gator were 16 when they organized the Baldies, an anti-racist skinhead group, five years ago. A few days later, over dinner at Chi-Chi’s, Joe, Gator, and their friend Chops talk about what the Baldies mean to them. “I think they know I’d give my life for them,” Joe says of his fellow skinheads, who currently number about 100 in the Twin Cities. “I know they’d do the same for me. I care about ‘em like they’re my brothers. They’re like a replacement family for me.” He smiles and nods at Gator. Gator nods back.

Joe is an intense 20-year old with short-cropped blond hair, light blue eyes, and a loud, nervous laugh. When he speaks he stares unwaveringly into your eyes, and the effect suggests a presence much larger than his stocky frame. He talks about partying and politics interchangeably; as he fluctuates between soft-spoken steadiness and fiery tirades about social injustice, he seems much too old for his years.

Both Joe and Gator seem most comfortable when they’re talking politics. They talk about changing the racist, classist system they were brought up in; their line is strident- combining traditional Midwestern populist distrust of the System with vaguely democratic-socialist ideas about how to fix it- but even as they’re giving speeches they’re looking to each other for approval: Is this right?

They’re less eager to talk about their families and their upbringing. The other Baldies, they’re family. Joe: “When you see a big group of skinheads all dressed the same, with the same hair, you just feel so relaxed. Goddamn, that’s true love to me, man. Because more than any other group- I don’t care who you are- skinheads will stand together. You can just look at them and know they’re gonna be with you. I’m down with them, they’re down with me. It’s like they’re automatically your brothers. We’ll take care of each other, and it feels so good.

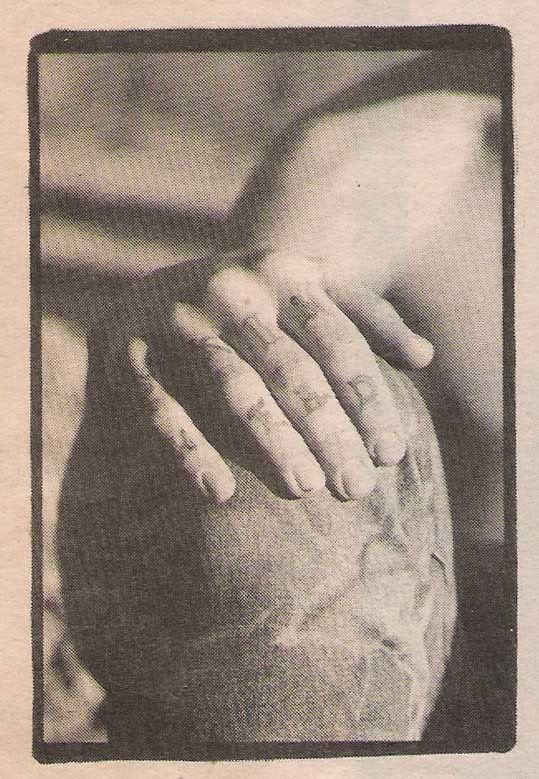

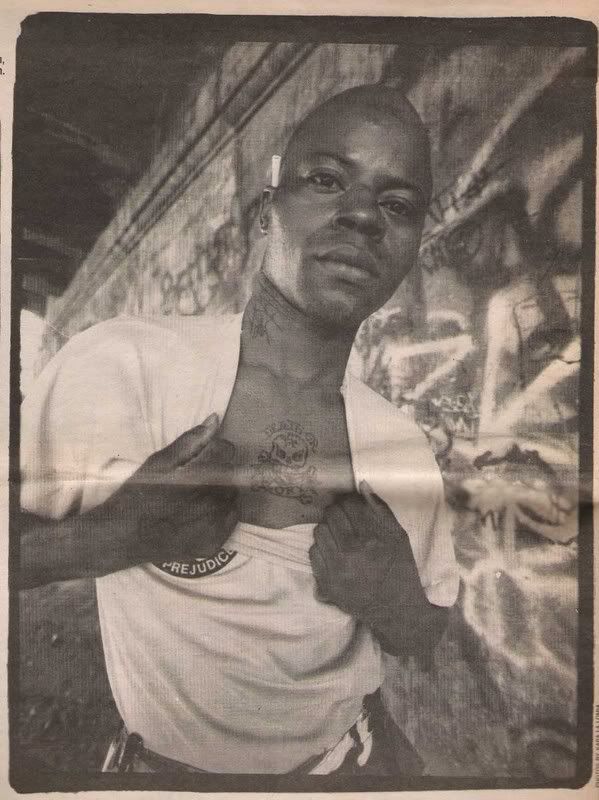

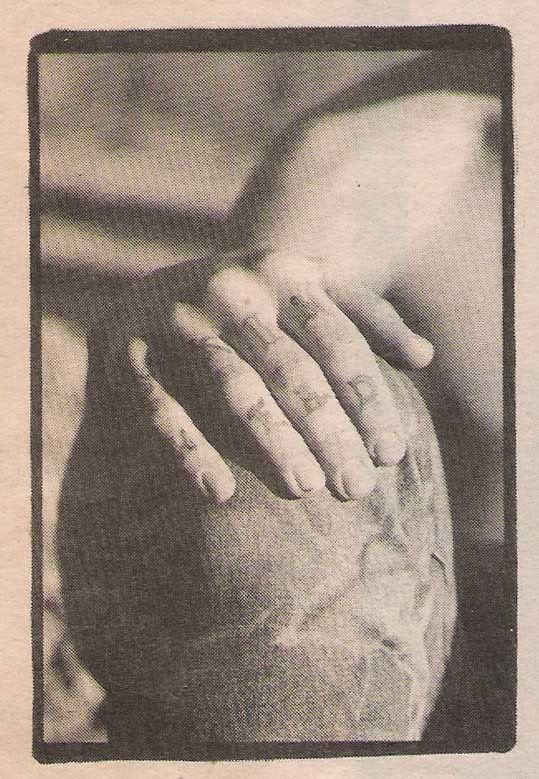

“I don’t think most people can say they have that sense of security.” Joe and Gator’s pal Chops has eight skinhead- theme tattoos on his arms, neck and torso; the letters ACAB tattooed across the knuckles of his left-hand stand for All Coppers Are Bastards. Now he chimes in: “How many people can walk into a city and know one person and then meet people who will put you up and be your brothers? It’s like that in every city I’ve been to where there’s real skinheads who are anti-racist. I’ve been put up and they’ve taken care of me while I worked my way.”

But what about the families they all came from before joining the skins? If you push a little they’ll talk about parents who divorced, and childhoods spent on welfare. But Joe and Gator insist they’re lucky compared to a lot of other kids they know. “My mom is my hero,” Joe says. “She’s a real successful lawyer.” Not by virtue of how much money she makes, he hastens to add. Because she helps people. How? He won’t elaborate; like nearly every other Baldie I talked to, he’s leery of giving enough details to allow his family to be identified. (Many didn’t want to appear in this story at all.) Joe says his own reticence stems from hate group threats his family received in the past when his real name appeared in StarTribune articles.

“People have this stereotype that all skinheads come from fucked up families,” he continues. “Most of their families aren’t bad, they’re just poor. Mine was real poor. My father left when I was two, and my mother and I were alone on welfare for five years until she married my stepfather. She was trying to make something of herself and make a better life for both of us. I remember that shit and I’m real proud of her. She beat the system, and now she helps people with legal problems work things out. Whether they’ve got money or not.”

Unlike Joe and Gator, Chops really hasn’t known much family besides the Baldies. At first he won’t say anything at all about it. He won’t disclose his age, or where he’s from, but little by little the story emerges anyway. His parents kicked him out of the house after he started using drugs in elementary school (“I didn’t wanna leave. I still wanna go home, you know”), and he’s spent the last several years bouncing between jails, reform schools, and lots of temporary jobs.

“I was having a lot of problems with drugs back then,” he says of the days after his parents kicked him out. “So I checked myself into treatment, and then I was straight for two and a half years. But I lost that again. But I’ve always held true to my beliefs and been true to my people, even though I always failed myself.”

Chops is doing okay for himself right now. He’s got a roommate to share expenses, and lately he’s had good luck landing factory work through a local temp agency. He hasn’t spoken to his dad in several years, and he’s only talked to his mom four times since he was kicked out. “I really want to see my sister,” he says at one point. Even after I moved out, I still took care of her as best as my situation allowed. She’s 17 now, and she’s working and doing pretty good. She’s got clothes now, and food, and she’s got a way to school, cuz I’m gonna sell her my car.

“She’s gonna finish high school and try to go to college. She knows I’ll beat the hell out of her if she fools around with anybody or drops out of school.”

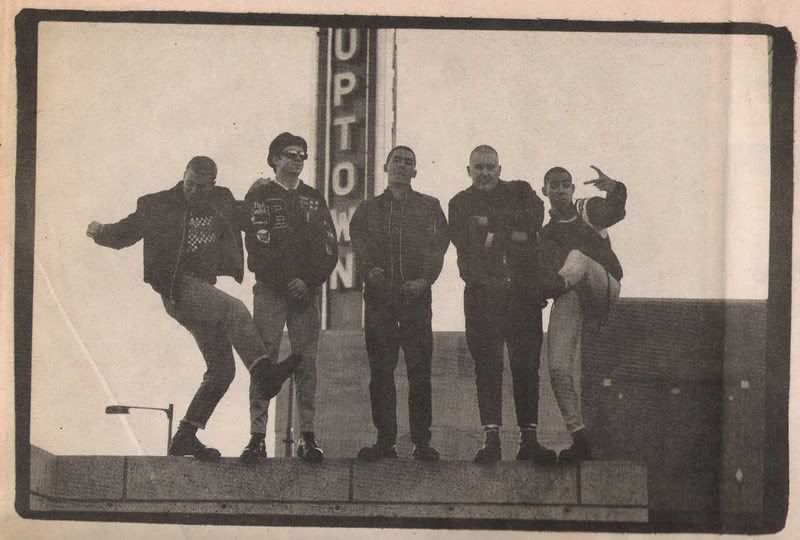

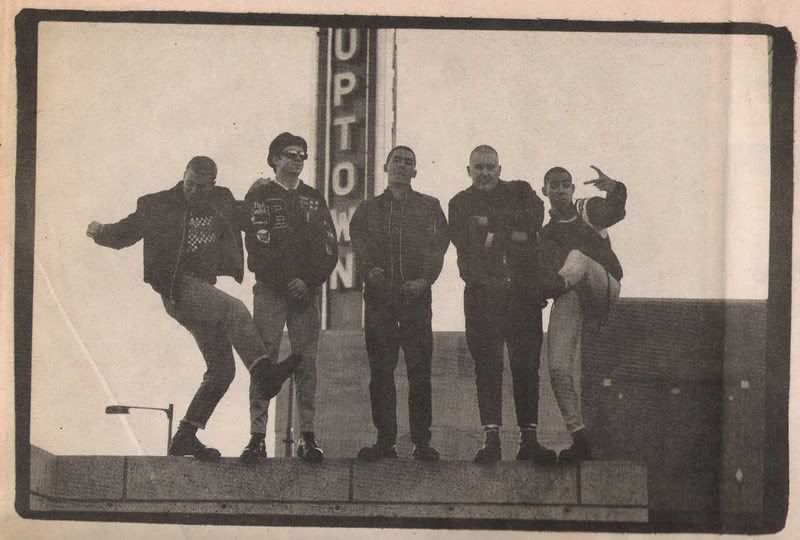

When they’re not riding bikes, listening to music, or working righteous violence against yuppies or the small contingent of racist skinheads from East St. Paul, the Baldies like to hang in the Uptown neighborhood. Their rough appearance and air of machismo makes them intimidating to a lot of Uptowners. That’s okay with them; as Joe puts it, “We’re an army for a righteous cause, and the best thing an army can do is look intimidating.”

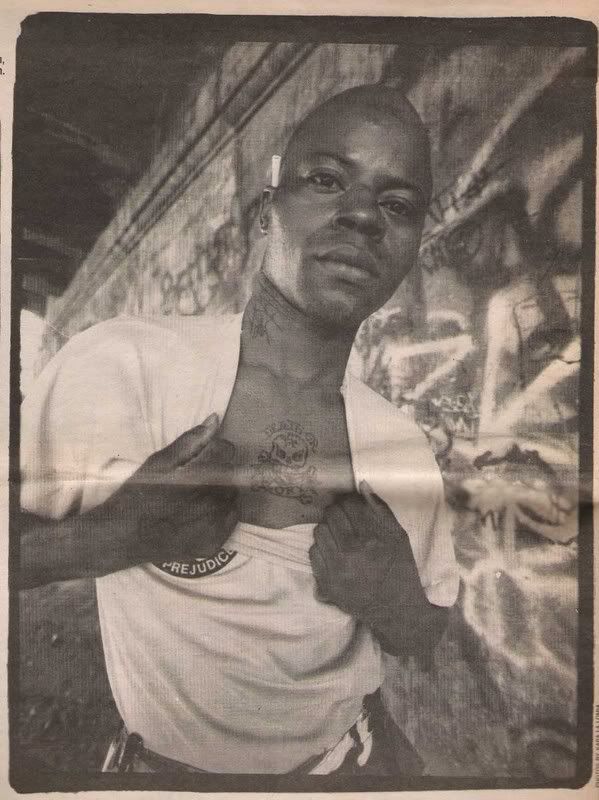

But they hate it when people confuse them with racist skinheads, a smaller group that’s nonetheless gotten far more media attention. “The media has created kind of a mass hysteria over nothing,” Joe fumes. “News 11, for godsakes, those morons. They showed a group of about eight of us and two of us were black, one was Oriental, and another was Native American, and they labeled us Nazi skinheads. I mean, how ignorant can you be?”

The skinhead movement began in Britain in the late 1960’s, the product of a cross-cultural merger between English working class mods and West Indian blacks who called themselves rude boys. The rude boys were into ska, a precursor of reggae that fused American R&B with Caribbean rhythms. The mods were into R&B; their look was clean but tough- not so different from the Baldies hanging out uptown right now.

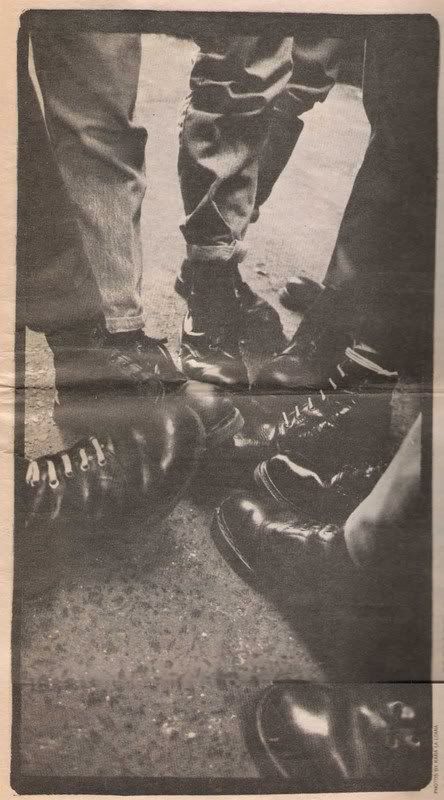

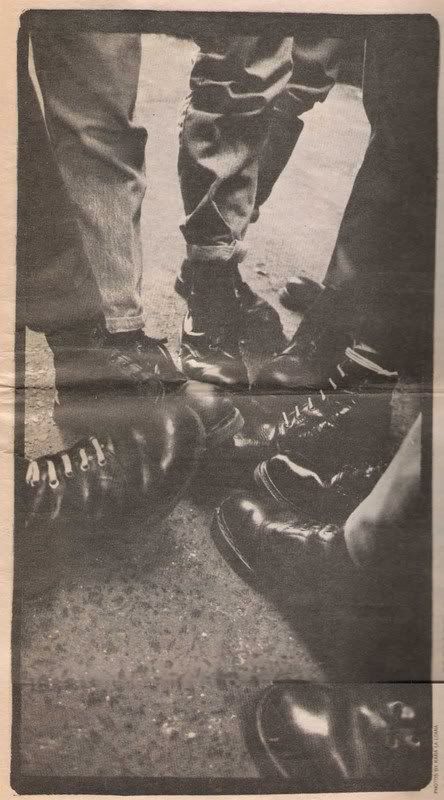

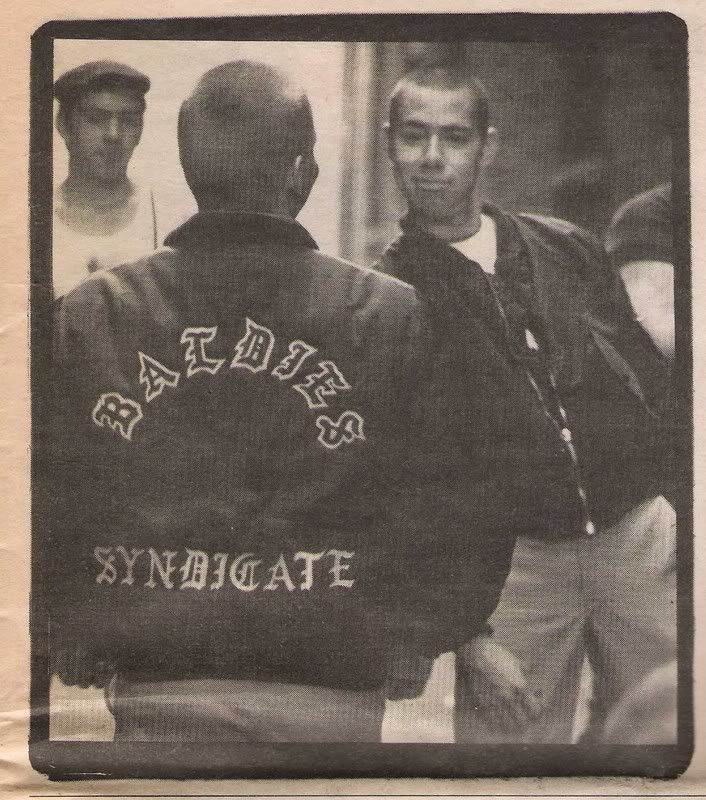

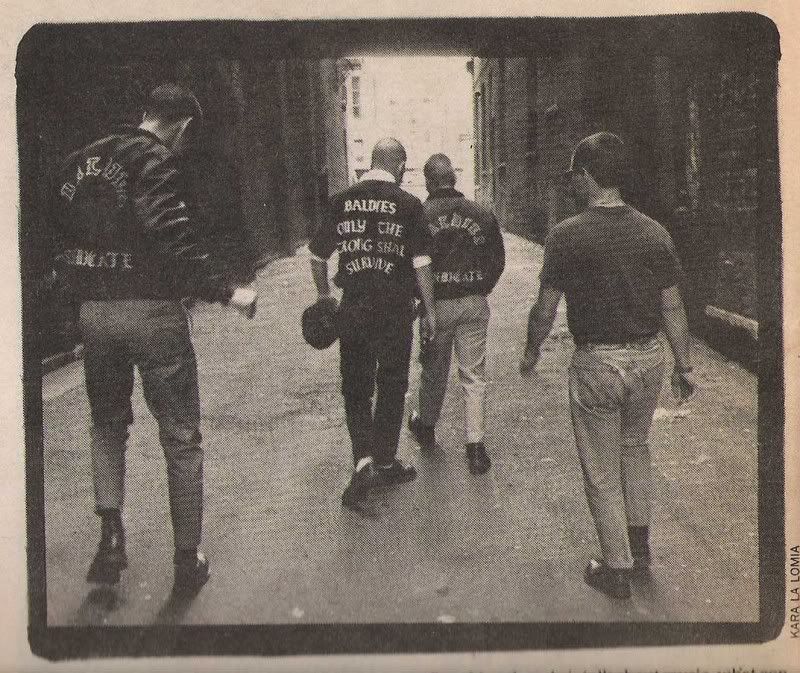

Whether you are a neo-Nazi or anti-racist, the dress code goes something like this: heavy jeans or work pants-sometimes held up by suspenders- button- down shirts (usually Fred Perry), black Doc Marten workboots (“Dr Marten” is the name of an English boot with reinforced toes), Finally, there is their trademark short-cropped hair. Besides being tough to grab in a fight, the short hair also served in the beginning to distinguish skins from hippies.

“It was almost a kind of anti-hippie movement,” Joe explains. “They didn’t like the style or the long hair. The short hair showed they took pride in their appearance. The hippies didn’t. I’m not saying they were wrong or anything; they just didn’t.

“You know they did create some change, but ultimately they had to realize they had to work within the system to effect any real change. Their, ‘Oh, we can have peace and love and go against our country and everybody can let all their hair grow and we’ll all have love-ins,’ that didn’t work. They were basically out there saying America sucks, and America doesn’t suck. The system sucks. I mean, I’m pro-Am to the point where I love my country and it’s gonna be here for a long time. But we’re gonna fight to make it better.”

The ‘70’s brought division to the traditional skinhead movement in Britain, as the economic woes of the time began to erode the group from within. “It got so there were a lot of working-class kids out of work and extremely frustrated with what was going on. That was when it became easy for them to start blaming their problems on the immigrants, who were mostly minorities,” Joe says.

Skinhead culture made little impression on the American imagination until punk came along in the late 1970’s. But punks who shaved their heads weren’t true skins, Gator says. “Punk is different. It’s more anti-establishment and stuff like that. Skinheads have pride in their country,” Gator says.

Joe nods, “Skinheads believe it’s their country, not the rich people’s. That’s why a lot of skinheads wear the flag; they mean the flag is theirs. I’m proud of the American working class, but I don’t hold any allegiance to this government. I don’t believe in all that.”

Joe says the problem is that the leaders in this country don’t know or care what the people need. “I was watching Dan Quayle and George Bush on television during the elections and they kept saying that they knew what ‘America needed.’ How do they know that? They’ve never fucking been there, man. They don’t know what it’s like to be poor. They don’t have any idea, and they don’t care. You know the government hates us. They don’t wanna see us unified because that means the working class will have power and could challenge the system, right?”

“Yeah,” echoes Chops. “That would mean the 5 percent who own 50 percent of the world would be challenged by the working class rising up to meet them. They don’t wanna see that, they don’t wanna see that at all. That’s why the boys in blue are always on us, because they’re the foot soldiers for the rich. They’re just the lackeys. Their job is the subjugation of the working class, to keep the poor down.”

It’s not just the cops, Joe repeats, it’s the system: “I’ve been straight for five years. The reason is because drugs and alcohol are not controlled in this country well enough. Why? Because it serves the government’s purpose of control. What better for the government than for Joe Blow to go out every night and take care of his frustrations with a few beers? That will work on his sense of reality, wear him down. Perfect. If you can keep people out of a sense of reality all the time, you won’t have to worry about them.”

The most conspicuous rap against the Baldies is their penchant for violence. They beat up a lot of people. But not randomly, they insist; it’s part of the program. “There’s a place and time for violence and it has to be righteous,” Joe says, looking down at the table. “I mean, I’m not just gonna go fight somebody. We’ve made mistakes, but- well, we’ve made a lot of mistakes. We’re only human. But I don’t want normal people to be afraid of me. They’ve got nothing to fear from me. Except for Nazis, I give everybody respect that gives me respect. You be good to me, I’ll be good to you. I want to get along with people. You know?”

Joe stops and Gator takes over, emphasizing that violence is righteous when you’re fighting for a cause: “Fighting racism is righteous. We don’t condone violence unless it’s righteous.”

So it’s righteous to beat up Nazis because they’re racist. Joe and Gator also agree that it’s all right to bash drug dealers because they “undermine the working class mission by taking them down with drugs.” As for other kinds of violence, Gator says earnestly, “We really are trying to stop the unrighteous fighting. We don’t wanna fight anybody but the Nazis, really.”

And the yuppies, sort of. They both know this is tougher to defend, but the Baldie crusade for betterment of the working class gets tiresome; real results are hard to come by. There are times when just punching a cocky yuppie in the face warms a Baldie’s heart. “Hey, I’m not gonna lie to you,” Joe agrees. “We’re kids. We make mistakes sometimes, you know. But that’s just part of growing up. You have your big drunk jocks who come out of Figlio’s and have heard how tough skinheads are, and they think they’ve got something to prove by fighting us. Same with yuppies downtown. I’m not gonna back down to a yuppie.”

When yuppies heckle Joe, “I’ll let them strike the first blow, but they’re gonna be on the ground real quick. I think they’re scum. I guess I can’t say that about all of them, but their attitudes are generally bad. All they care about is being rich and acquiring as much as they can and showing it off. They don’t care about sexism or racism or anything but themselves and I just don’t have time for that. They’re like bugs clogging up a fan.”

Not everybody understands the Baldies mission the way they do. “This guy asked me once if I would beat a guy up for $100,” Joe says. “He said, ‘Hey, what would you do to somebody for $100? Break his arm, maybe?’ That’s just like somebody saying ‘Hi, I think you’re really ignorant. Would you be a thug for me?’ That’s just not what we’re about. That’s not what I wanna be. I have respect for violence.

People fear violence in this city, but the reality is you can either cower from it or live with it. Cuz it’s not gonna go away. We skinheads are just a reflection of inner-city life. We were created from the inner-city underclass, and the violence you lay on us was already there. But there’s respect and dignity, too. We have to get along because we’re all in this together. The whole saying is ‘United and Strong’. It means everybody. Not just blacks and whites, but everybody- if we ever want to have a decent society.”

Righteous or not, the Baldies are just another gang in the eyes of the cops. “My basic feeling about the skinheads is that they’re all equally violent,” says Gang Unit officer Mike Schoeben. “It seems that even the non-racist ones have a philosophy of life that says if you are somehow above the working class or part of the establishment, then they don’t like you. That is their form of prejudice.

“We’ve classified them as a white gang but it’s still hard to get a handle on who they are really. They do fit our criteria, though: dressing alike, same philosophy, and fighting among themselves, you know.”

Bring up the word “gang” around Joe and his voice gets shrill: “We are not a gang. We don’t do drugs and we don’t sell drugs. We don’t carry weapons and we don’t commit crimes. If you deal and you’re a Baldie, you’re out. We just won’t tolerate it. I mean the only crimes we condone are righteous acts of violence. Those are necessary things.

“Our relationship with the police is an example of something that could use a hell of a lot of improvement,” he says. Gator and Joe both claim to know Baldies who’ve been picked up by cops Uptown and driven down to the banks of the Mississippi, where they were called names like “nigger lover” and “communist” and thrown out of the squad car. Says Joe: “I know this guy who had his legs kicked out from under him by one cop while his partner kicked him in the chest and said not to come around Uptown for a long time unless he wanted more of the same.”

They say a few cops, mostly minorities, give them a break out of sympathy with that they stand for. “Some of the minority cops give us a lot more room, because they know what we’re about. Like if there’s a fight between us and the Nazis, they’ll say, “Okay, are there any Baldies here?” and we’ll say ‘yeah,’ and they’ll let us go and arrest the Nazis. But that doesn’t happen very often.”

Ironically, a lot of the people the Baldies are currently looking to bash were once part of their fold. In the beginning, the Baldies were just a bunch of adolescent guys looking to belong to something; almost everyone was welcome. “There weren’t any Nazis around here in the beginning,” says Joe, “but about six or seven months later a lot of kids started shaving their heads and hanging out with us. But they were dorks, man. They didn’t know what it was all about, so we kicked ‘em out. That’s how the White Knights (the first local group of neo-Nazi skins) basically started.

“We tried to talk to them and educate them for a while, but they were going around in groups attacking minorities. I mean, like seven guys with baseball bats attacking one lone Indian or black man. We just got sick of it, and we told them that every time we saw them we were gonna bash them and we did. They were totally disbanded within two weeks.” But the White Knights soon regrouped, dressing the same way as their anti-racist counterparts but espousing white pride and racial violence. Joe estimates there are 20 or 30 Nazi skins in the Twin Cities now, but only 10 or so who are very active.

Though the Minneapolis/ St. Paul metro has nowhere near the hate crime statistics of cities like Los Angeles or Chicago, it’s had its share of racist skinhead attacks. Last year a group of youths identified as Nazi skinheads beat a 14-year-old South Minneapolis boy with a wooden stick wrapped in barbed wire. According to police reports, the boy and several friends were playing basketball in a backyard on Emerson and 32nd when one of them exchanged words with one of the suspects. The man returned minutes later with five or six others, shouting racial slurs.

Just a few months earlier, a 24-year old man was chased by at least four Nazi skinheads after they saw him walking to Williams Nightclub in Uptown. Sidney Payton told the StarTribune that he was walking to the club about 11:00 on a Saturday night when the group began chasing him carrying a hammer and a board and shouting, “Hey, look at that nigger over there! Get the nigger!”

Neo-nazi skinheads are the fastest growing hate group in America, says Morton Ryweck, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council Anti- Defamation League of Minnesota and the Dakotas. In November 1987, the League estimated the neo- Nazi skins population at “several hundred.” Those numbers have since grown to over 3,000 members in 30 states.

Many Nazi skinheads have been recruited by such well-known hate groups as the Ku Klux Klan and White Aryan Resistance (WAR), whose membership has thinned over the last decade. One of the principal figures behind the revitalization of hate groups is a 50-year old TV repairman from Fallbrook, California, named Tom Metzger. As former Grand Dragon of California’s Ku Klux Klan and leader of the White Aryan Resistance, Metzger is one of the most visible hatemongers in the nation.

He is also one of the most powerful, for in perfecting and preaching his own brand of bigotry, Metzger has also mastered the art of recruiting. He chooses his boot-boys carefully; most of them share a generalized rage at the world and a need to belong. Couching his message in the rhetoric of white power pride, Metzger is able to lure not only bona fide racists, but many of the same youths who might as easily have joined a group like the Baldies. But instead of railing at oppressive government, Metzger preaches about a world where the future of the white ruling class is threatened by racial integration. He and his son John tell their followers that violence and bigotry actually amount to self-defense against the Jews and people of color trying to wrest away control of the nation.

Many of these kids, Gator says, don’t even understand the racism in what they’re doing. “A lot of these guys,” he says, “all they do is get up in the morning and look in the mirror and say, ‘Yeah, white pride!’ and go out there. It’s amazing how many of these Nazi kids have been kicked out of their home, things like that. The white power movement acts like it’s giving these little kids what they need. The leaders tell them they love them and care about them, and these kids just get sucked in.”

In citing their growing numbers, Ryweck is also quick to point out that neo-Nazi skinheads are not a major force in Minnesota. He adds that the media has created the alarmist atmosphere over the racist skinhead threat, because they fail to distinguish between the two groups of skins.

Sitting at a table in Chi-Chi’s downtown, Chops pulls on my sleeve. He looks overcome with self-consciousness. “Hey,” he says, “Am I dressed okay to be in here? He’s wearing jeans, a black t-shirt, and a black flight jacket.

Joe tries to reassure him by making a joke of it: “Shit, man, there’s crumbs on my chair.” He makes a dismissive gesture. Chops doesn’t seem reassured. “Man, I’m sitting two feet from a fuckin’ fountain”.

After Chops is finally assured that they’ll serve him in spite of his clothes, I ask all three of them what they see themselves doing in a few years. What about girlfriends, families of their own?

“I’ve had some serious relationships,” Joe volunteers. “I had one for about a year and a half, and it’s really hard. Quite honestly, it didn’t work out because I’m a skinhead. It’s a really big part of my life, and she didn’t get it.”

Gator giggles. “It’s the same for me,” he says. “If I want to go out with a girl, it’s to have fun, and if I have a hard time it’s like… later. I just wanna have fun. This is kinda like a job, being a Baldie. And it’s hard, cuz we don’t have leaders, so we have to do everything ourselves.”

Chops isn’t quite so serious. He’s got his girl’s name tattooed on his chest, and he likes to go dancing. “It’s just good music and fun to me a lot of the time,” he says of the Baldie life. “I like listening to International Jet Set a lot (they mean the English Beat- ed.). They’re a ska band- a really good two- tone sound.

“You can talk about skinheads being crusaders and everything, but when they get together the first thing they do is talk about music, what concerts they’ve seen and stuff. And they trade things with each other, like records. The thing I’d tell people about skinheads is that if they see them, they shouldn’t be afraid. They should just walk up and tell ‘em where the good parties are.”

Joe knows the Baldie life can’t stay the same forever. “I realize there’s gonna be a time when I get older and I’m gonna have people that I care about, and who care about me, and the risk just won’t be worth it. Right now I’m going to school and I’m real interested in social work. I’m getting a humanities background.

“I still want to do something that involves fighting racism when I get older. And even if I’m not working in a factory or something like that, I still want to be doing something that contributes to the working class, because that’s where my roots are. That’s where I came from.”

---------

This article first appeared in CITY PAGES V. 12 #478 (January 31, 1990) pg. 6

Special thanks to Kieran of the Baldies for an original copy of this article. Scanning and transcription by Dan (RASH- NYC). Special thanks to Edith for help with scanning.

THE LOST BOYS

Anti-racism, brotherhood and righteous violence: the world according to the Baldies.

By Meleah Maynard

Photos by Kara LaLomia

When Max was in high school, he went to a tattoo parlor and had the word SKIN imprinted inside his lower lip. “Oh, yeah, it hurt like hell at the time,” he grimaces. Without much prompting he sets aside his burger and rolls down his lip to expose the black lettering inside. “I got it because it’s something I believe in,” he says. “Once a skin, always a skin. It’s something that will always be there. It’s a matter of pride.”

After he finishes his burger, Max thinks better of his boast. “Can you change my name in the story?” he asks. “I’m afraid my mom would get made if she knew.” Okay- Max isn’t his real name.

Max’s friends Joe Hawkins and Gator were 16 when they organized the Baldies, an anti-racist skinhead group, five years ago. A few days later, over dinner at Chi-Chi’s, Joe, Gator, and their friend Chops talk about what the Baldies mean to them. “I think they know I’d give my life for them,” Joe says of his fellow skinheads, who currently number about 100 in the Twin Cities. “I know they’d do the same for me. I care about ‘em like they’re my brothers. They’re like a replacement family for me.” He smiles and nods at Gator. Gator nods back.

Joe is an intense 20-year old with short-cropped blond hair, light blue eyes, and a loud, nervous laugh. When he speaks he stares unwaveringly into your eyes, and the effect suggests a presence much larger than his stocky frame. He talks about partying and politics interchangeably; as he fluctuates between soft-spoken steadiness and fiery tirades about social injustice, he seems much too old for his years.

Both Joe and Gator seem most comfortable when they’re talking politics. They talk about changing the racist, classist system they were brought up in; their line is strident- combining traditional Midwestern populist distrust of the System with vaguely democratic-socialist ideas about how to fix it- but even as they’re giving speeches they’re looking to each other for approval: Is this right?

They’re less eager to talk about their families and their upbringing. The other Baldies, they’re family. Joe: “When you see a big group of skinheads all dressed the same, with the same hair, you just feel so relaxed. Goddamn, that’s true love to me, man. Because more than any other group- I don’t care who you are- skinheads will stand together. You can just look at them and know they’re gonna be with you. I’m down with them, they’re down with me. It’s like they’re automatically your brothers. We’ll take care of each other, and it feels so good.

“I don’t think most people can say they have that sense of security.” Joe and Gator’s pal Chops has eight skinhead- theme tattoos on his arms, neck and torso; the letters ACAB tattooed across the knuckles of his left-hand stand for All Coppers Are Bastards. Now he chimes in: “How many people can walk into a city and know one person and then meet people who will put you up and be your brothers? It’s like that in every city I’ve been to where there’s real skinheads who are anti-racist. I’ve been put up and they’ve taken care of me while I worked my way.”

But what about the families they all came from before joining the skins? If you push a little they’ll talk about parents who divorced, and childhoods spent on welfare. But Joe and Gator insist they’re lucky compared to a lot of other kids they know. “My mom is my hero,” Joe says. “She’s a real successful lawyer.” Not by virtue of how much money she makes, he hastens to add. Because she helps people. How? He won’t elaborate; like nearly every other Baldie I talked to, he’s leery of giving enough details to allow his family to be identified. (Many didn’t want to appear in this story at all.) Joe says his own reticence stems from hate group threats his family received in the past when his real name appeared in StarTribune articles.

“People have this stereotype that all skinheads come from fucked up families,” he continues. “Most of their families aren’t bad, they’re just poor. Mine was real poor. My father left when I was two, and my mother and I were alone on welfare for five years until she married my stepfather. She was trying to make something of herself and make a better life for both of us. I remember that shit and I’m real proud of her. She beat the system, and now she helps people with legal problems work things out. Whether they’ve got money or not.”

Unlike Joe and Gator, Chops really hasn’t known much family besides the Baldies. At first he won’t say anything at all about it. He won’t disclose his age, or where he’s from, but little by little the story emerges anyway. His parents kicked him out of the house after he started using drugs in elementary school (“I didn’t wanna leave. I still wanna go home, you know”), and he’s spent the last several years bouncing between jails, reform schools, and lots of temporary jobs.

“I was having a lot of problems with drugs back then,” he says of the days after his parents kicked him out. “So I checked myself into treatment, and then I was straight for two and a half years. But I lost that again. But I’ve always held true to my beliefs and been true to my people, even though I always failed myself.”

Chops is doing okay for himself right now. He’s got a roommate to share expenses, and lately he’s had good luck landing factory work through a local temp agency. He hasn’t spoken to his dad in several years, and he’s only talked to his mom four times since he was kicked out. “I really want to see my sister,” he says at one point. Even after I moved out, I still took care of her as best as my situation allowed. She’s 17 now, and she’s working and doing pretty good. She’s got clothes now, and food, and she’s got a way to school, cuz I’m gonna sell her my car.

“She’s gonna finish high school and try to go to college. She knows I’ll beat the hell out of her if she fools around with anybody or drops out of school.”

When they’re not riding bikes, listening to music, or working righteous violence against yuppies or the small contingent of racist skinheads from East St. Paul, the Baldies like to hang in the Uptown neighborhood. Their rough appearance and air of machismo makes them intimidating to a lot of Uptowners. That’s okay with them; as Joe puts it, “We’re an army for a righteous cause, and the best thing an army can do is look intimidating.”

But they hate it when people confuse them with racist skinheads, a smaller group that’s nonetheless gotten far more media attention. “The media has created kind of a mass hysteria over nothing,” Joe fumes. “News 11, for godsakes, those morons. They showed a group of about eight of us and two of us were black, one was Oriental, and another was Native American, and they labeled us Nazi skinheads. I mean, how ignorant can you be?”

The skinhead movement began in Britain in the late 1960’s, the product of a cross-cultural merger between English working class mods and West Indian blacks who called themselves rude boys. The rude boys were into ska, a precursor of reggae that fused American R&B with Caribbean rhythms. The mods were into R&B; their look was clean but tough- not so different from the Baldies hanging out uptown right now.

Whether you are a neo-Nazi or anti-racist, the dress code goes something like this: heavy jeans or work pants-sometimes held up by suspenders- button- down shirts (usually Fred Perry), black Doc Marten workboots (“Dr Marten” is the name of an English boot with reinforced toes), Finally, there is their trademark short-cropped hair. Besides being tough to grab in a fight, the short hair also served in the beginning to distinguish skins from hippies.

“It was almost a kind of anti-hippie movement,” Joe explains. “They didn’t like the style or the long hair. The short hair showed they took pride in their appearance. The hippies didn’t. I’m not saying they were wrong or anything; they just didn’t.

“You know they did create some change, but ultimately they had to realize they had to work within the system to effect any real change. Their, ‘Oh, we can have peace and love and go against our country and everybody can let all their hair grow and we’ll all have love-ins,’ that didn’t work. They were basically out there saying America sucks, and America doesn’t suck. The system sucks. I mean, I’m pro-Am to the point where I love my country and it’s gonna be here for a long time. But we’re gonna fight to make it better.”

The ‘70’s brought division to the traditional skinhead movement in Britain, as the economic woes of the time began to erode the group from within. “It got so there were a lot of working-class kids out of work and extremely frustrated with what was going on. That was when it became easy for them to start blaming their problems on the immigrants, who were mostly minorities,” Joe says.

Skinhead culture made little impression on the American imagination until punk came along in the late 1970’s. But punks who shaved their heads weren’t true skins, Gator says. “Punk is different. It’s more anti-establishment and stuff like that. Skinheads have pride in their country,” Gator says.

Joe nods, “Skinheads believe it’s their country, not the rich people’s. That’s why a lot of skinheads wear the flag; they mean the flag is theirs. I’m proud of the American working class, but I don’t hold any allegiance to this government. I don’t believe in all that.”

Joe says the problem is that the leaders in this country don’t know or care what the people need. “I was watching Dan Quayle and George Bush on television during the elections and they kept saying that they knew what ‘America needed.’ How do they know that? They’ve never fucking been there, man. They don’t know what it’s like to be poor. They don’t have any idea, and they don’t care. You know the government hates us. They don’t wanna see us unified because that means the working class will have power and could challenge the system, right?”

“Yeah,” echoes Chops. “That would mean the 5 percent who own 50 percent of the world would be challenged by the working class rising up to meet them. They don’t wanna see that, they don’t wanna see that at all. That’s why the boys in blue are always on us, because they’re the foot soldiers for the rich. They’re just the lackeys. Their job is the subjugation of the working class, to keep the poor down.”

It’s not just the cops, Joe repeats, it’s the system: “I’ve been straight for five years. The reason is because drugs and alcohol are not controlled in this country well enough. Why? Because it serves the government’s purpose of control. What better for the government than for Joe Blow to go out every night and take care of his frustrations with a few beers? That will work on his sense of reality, wear him down. Perfect. If you can keep people out of a sense of reality all the time, you won’t have to worry about them.”

The most conspicuous rap against the Baldies is their penchant for violence. They beat up a lot of people. But not randomly, they insist; it’s part of the program. “There’s a place and time for violence and it has to be righteous,” Joe says, looking down at the table. “I mean, I’m not just gonna go fight somebody. We’ve made mistakes, but- well, we’ve made a lot of mistakes. We’re only human. But I don’t want normal people to be afraid of me. They’ve got nothing to fear from me. Except for Nazis, I give everybody respect that gives me respect. You be good to me, I’ll be good to you. I want to get along with people. You know?”

Joe stops and Gator takes over, emphasizing that violence is righteous when you’re fighting for a cause: “Fighting racism is righteous. We don’t condone violence unless it’s righteous.”

So it’s righteous to beat up Nazis because they’re racist. Joe and Gator also agree that it’s all right to bash drug dealers because they “undermine the working class mission by taking them down with drugs.” As for other kinds of violence, Gator says earnestly, “We really are trying to stop the unrighteous fighting. We don’t wanna fight anybody but the Nazis, really.”

And the yuppies, sort of. They both know this is tougher to defend, but the Baldie crusade for betterment of the working class gets tiresome; real results are hard to come by. There are times when just punching a cocky yuppie in the face warms a Baldie’s heart. “Hey, I’m not gonna lie to you,” Joe agrees. “We’re kids. We make mistakes sometimes, you know. But that’s just part of growing up. You have your big drunk jocks who come out of Figlio’s and have heard how tough skinheads are, and they think they’ve got something to prove by fighting us. Same with yuppies downtown. I’m not gonna back down to a yuppie.”

When yuppies heckle Joe, “I’ll let them strike the first blow, but they’re gonna be on the ground real quick. I think they’re scum. I guess I can’t say that about all of them, but their attitudes are generally bad. All they care about is being rich and acquiring as much as they can and showing it off. They don’t care about sexism or racism or anything but themselves and I just don’t have time for that. They’re like bugs clogging up a fan.”

Not everybody understands the Baldies mission the way they do. “This guy asked me once if I would beat a guy up for $100,” Joe says. “He said, ‘Hey, what would you do to somebody for $100? Break his arm, maybe?’ That’s just like somebody saying ‘Hi, I think you’re really ignorant. Would you be a thug for me?’ That’s just not what we’re about. That’s not what I wanna be. I have respect for violence.

People fear violence in this city, but the reality is you can either cower from it or live with it. Cuz it’s not gonna go away. We skinheads are just a reflection of inner-city life. We were created from the inner-city underclass, and the violence you lay on us was already there. But there’s respect and dignity, too. We have to get along because we’re all in this together. The whole saying is ‘United and Strong’. It means everybody. Not just blacks and whites, but everybody- if we ever want to have a decent society.”

Righteous or not, the Baldies are just another gang in the eyes of the cops. “My basic feeling about the skinheads is that they’re all equally violent,” says Gang Unit officer Mike Schoeben. “It seems that even the non-racist ones have a philosophy of life that says if you are somehow above the working class or part of the establishment, then they don’t like you. That is their form of prejudice.

“We’ve classified them as a white gang but it’s still hard to get a handle on who they are really. They do fit our criteria, though: dressing alike, same philosophy, and fighting among themselves, you know.”

Bring up the word “gang” around Joe and his voice gets shrill: “We are not a gang. We don’t do drugs and we don’t sell drugs. We don’t carry weapons and we don’t commit crimes. If you deal and you’re a Baldie, you’re out. We just won’t tolerate it. I mean the only crimes we condone are righteous acts of violence. Those are necessary things.

“Our relationship with the police is an example of something that could use a hell of a lot of improvement,” he says. Gator and Joe both claim to know Baldies who’ve been picked up by cops Uptown and driven down to the banks of the Mississippi, where they were called names like “nigger lover” and “communist” and thrown out of the squad car. Says Joe: “I know this guy who had his legs kicked out from under him by one cop while his partner kicked him in the chest and said not to come around Uptown for a long time unless he wanted more of the same.”

They say a few cops, mostly minorities, give them a break out of sympathy with that they stand for. “Some of the minority cops give us a lot more room, because they know what we’re about. Like if there’s a fight between us and the Nazis, they’ll say, “Okay, are there any Baldies here?” and we’ll say ‘yeah,’ and they’ll let us go and arrest the Nazis. But that doesn’t happen very often.”

Ironically, a lot of the people the Baldies are currently looking to bash were once part of their fold. In the beginning, the Baldies were just a bunch of adolescent guys looking to belong to something; almost everyone was welcome. “There weren’t any Nazis around here in the beginning,” says Joe, “but about six or seven months later a lot of kids started shaving their heads and hanging out with us. But they were dorks, man. They didn’t know what it was all about, so we kicked ‘em out. That’s how the White Knights (the first local group of neo-Nazi skins) basically started.

“We tried to talk to them and educate them for a while, but they were going around in groups attacking minorities. I mean, like seven guys with baseball bats attacking one lone Indian or black man. We just got sick of it, and we told them that every time we saw them we were gonna bash them and we did. They were totally disbanded within two weeks.” But the White Knights soon regrouped, dressing the same way as their anti-racist counterparts but espousing white pride and racial violence. Joe estimates there are 20 or 30 Nazi skins in the Twin Cities now, but only 10 or so who are very active.

Though the Minneapolis/ St. Paul metro has nowhere near the hate crime statistics of cities like Los Angeles or Chicago, it’s had its share of racist skinhead attacks. Last year a group of youths identified as Nazi skinheads beat a 14-year-old South Minneapolis boy with a wooden stick wrapped in barbed wire. According to police reports, the boy and several friends were playing basketball in a backyard on Emerson and 32nd when one of them exchanged words with one of the suspects. The man returned minutes later with five or six others, shouting racial slurs.

Just a few months earlier, a 24-year old man was chased by at least four Nazi skinheads after they saw him walking to Williams Nightclub in Uptown. Sidney Payton told the StarTribune that he was walking to the club about 11:00 on a Saturday night when the group began chasing him carrying a hammer and a board and shouting, “Hey, look at that nigger over there! Get the nigger!”

Neo-nazi skinheads are the fastest growing hate group in America, says Morton Ryweck, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council Anti- Defamation League of Minnesota and the Dakotas. In November 1987, the League estimated the neo- Nazi skins population at “several hundred.” Those numbers have since grown to over 3,000 members in 30 states.

Many Nazi skinheads have been recruited by such well-known hate groups as the Ku Klux Klan and White Aryan Resistance (WAR), whose membership has thinned over the last decade. One of the principal figures behind the revitalization of hate groups is a 50-year old TV repairman from Fallbrook, California, named Tom Metzger. As former Grand Dragon of California’s Ku Klux Klan and leader of the White Aryan Resistance, Metzger is one of the most visible hatemongers in the nation.

He is also one of the most powerful, for in perfecting and preaching his own brand of bigotry, Metzger has also mastered the art of recruiting. He chooses his boot-boys carefully; most of them share a generalized rage at the world and a need to belong. Couching his message in the rhetoric of white power pride, Metzger is able to lure not only bona fide racists, but many of the same youths who might as easily have joined a group like the Baldies. But instead of railing at oppressive government, Metzger preaches about a world where the future of the white ruling class is threatened by racial integration. He and his son John tell their followers that violence and bigotry actually amount to self-defense against the Jews and people of color trying to wrest away control of the nation.

Many of these kids, Gator says, don’t even understand the racism in what they’re doing. “A lot of these guys,” he says, “all they do is get up in the morning and look in the mirror and say, ‘Yeah, white pride!’ and go out there. It’s amazing how many of these Nazi kids have been kicked out of their home, things like that. The white power movement acts like it’s giving these little kids what they need. The leaders tell them they love them and care about them, and these kids just get sucked in.”

In citing their growing numbers, Ryweck is also quick to point out that neo-Nazi skinheads are not a major force in Minnesota. He adds that the media has created the alarmist atmosphere over the racist skinhead threat, because they fail to distinguish between the two groups of skins.

Sitting at a table in Chi-Chi’s downtown, Chops pulls on my sleeve. He looks overcome with self-consciousness. “Hey,” he says, “Am I dressed okay to be in here? He’s wearing jeans, a black t-shirt, and a black flight jacket.

Joe tries to reassure him by making a joke of it: “Shit, man, there’s crumbs on my chair.” He makes a dismissive gesture. Chops doesn’t seem reassured. “Man, I’m sitting two feet from a fuckin’ fountain”.

After Chops is finally assured that they’ll serve him in spite of his clothes, I ask all three of them what they see themselves doing in a few years. What about girlfriends, families of their own?

“I’ve had some serious relationships,” Joe volunteers. “I had one for about a year and a half, and it’s really hard. Quite honestly, it didn’t work out because I’m a skinhead. It’s a really big part of my life, and she didn’t get it.”

Gator giggles. “It’s the same for me,” he says. “If I want to go out with a girl, it’s to have fun, and if I have a hard time it’s like… later. I just wanna have fun. This is kinda like a job, being a Baldie. And it’s hard, cuz we don’t have leaders, so we have to do everything ourselves.”

Chops isn’t quite so serious. He’s got his girl’s name tattooed on his chest, and he likes to go dancing. “It’s just good music and fun to me a lot of the time,” he says of the Baldie life. “I like listening to International Jet Set a lot (they mean the English Beat- ed.). They’re a ska band- a really good two- tone sound.

“You can talk about skinheads being crusaders and everything, but when they get together the first thing they do is talk about music, what concerts they’ve seen and stuff. And they trade things with each other, like records. The thing I’d tell people about skinheads is that if they see them, they shouldn’t be afraid. They should just walk up and tell ‘em where the good parties are.”

Joe knows the Baldie life can’t stay the same forever. “I realize there’s gonna be a time when I get older and I’m gonna have people that I care about, and who care about me, and the risk just won’t be worth it. Right now I’m going to school and I’m real interested in social work. I’m getting a humanities background.

“I still want to do something that involves fighting racism when I get older. And even if I’m not working in a factory or something like that, I still want to be doing something that contributes to the working class, because that’s where my roots are. That’s where I came from.”

---------

This article first appeared in CITY PAGES V. 12 #478 (January 31, 1990) pg. 6

Special thanks to Kieran of the Baldies for an original copy of this article. Scanning and transcription by Dan (RASH- NYC). Special thanks to Edith for help with scanning.